Writing Effective IEP Goals

Four Components of Effective IEP Goals

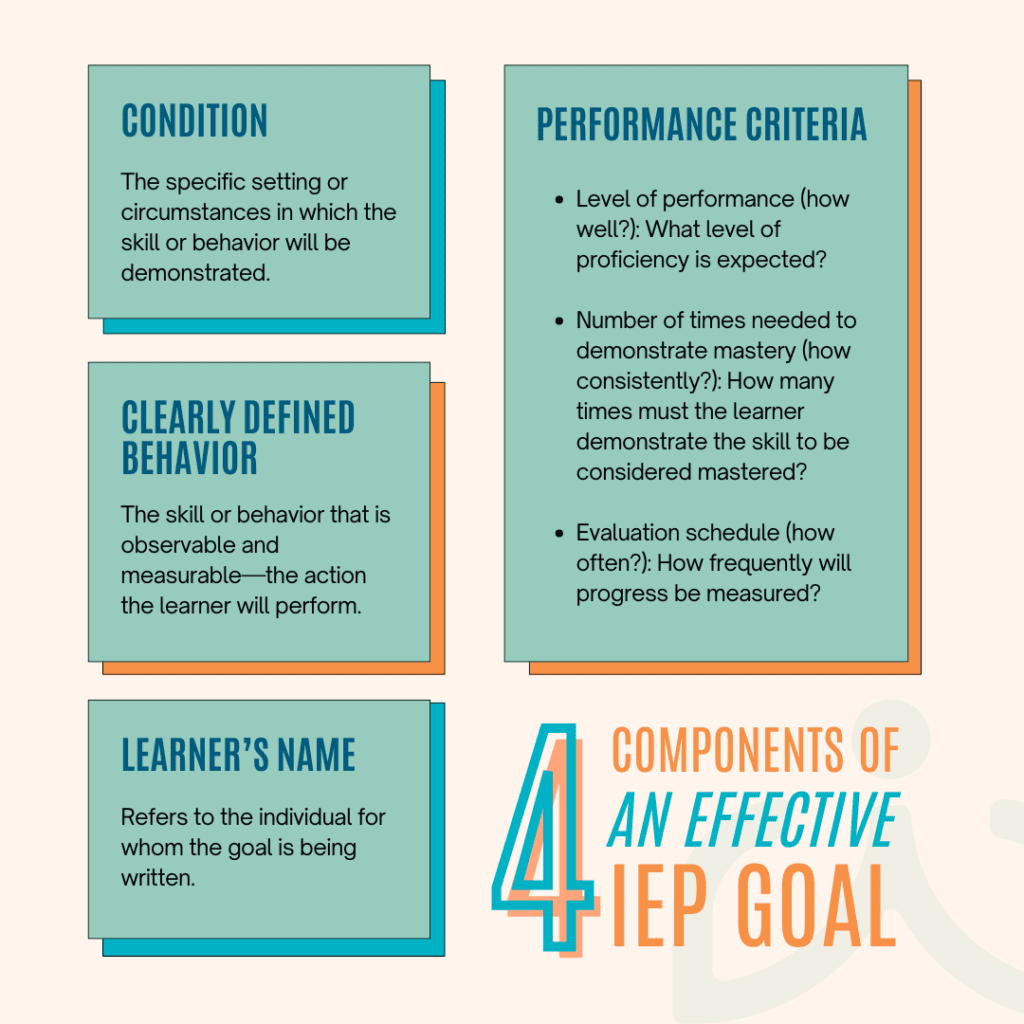

- Condition: The specific setting or circumstances in which the skill or behavior will be demonstrated.

- Learner’s Name: Refers to the individual for whom the goal is being written.

- Clearly Defined Behavior: The skill or behavior that is observable and measurable—the action the learner will perform.

- Performance Criteria: This includes three parts:

- Level of performance (how well?): What level of proficiency is expected?

- Number of times needed to demonstrate mastery (how consistently?): How many times must the learner demonstrate the skill to be considered mastered?

- Evaluation schedule (how often?): How frequently will progress be measured?

A Common Pitfall When Writing IEP Goals

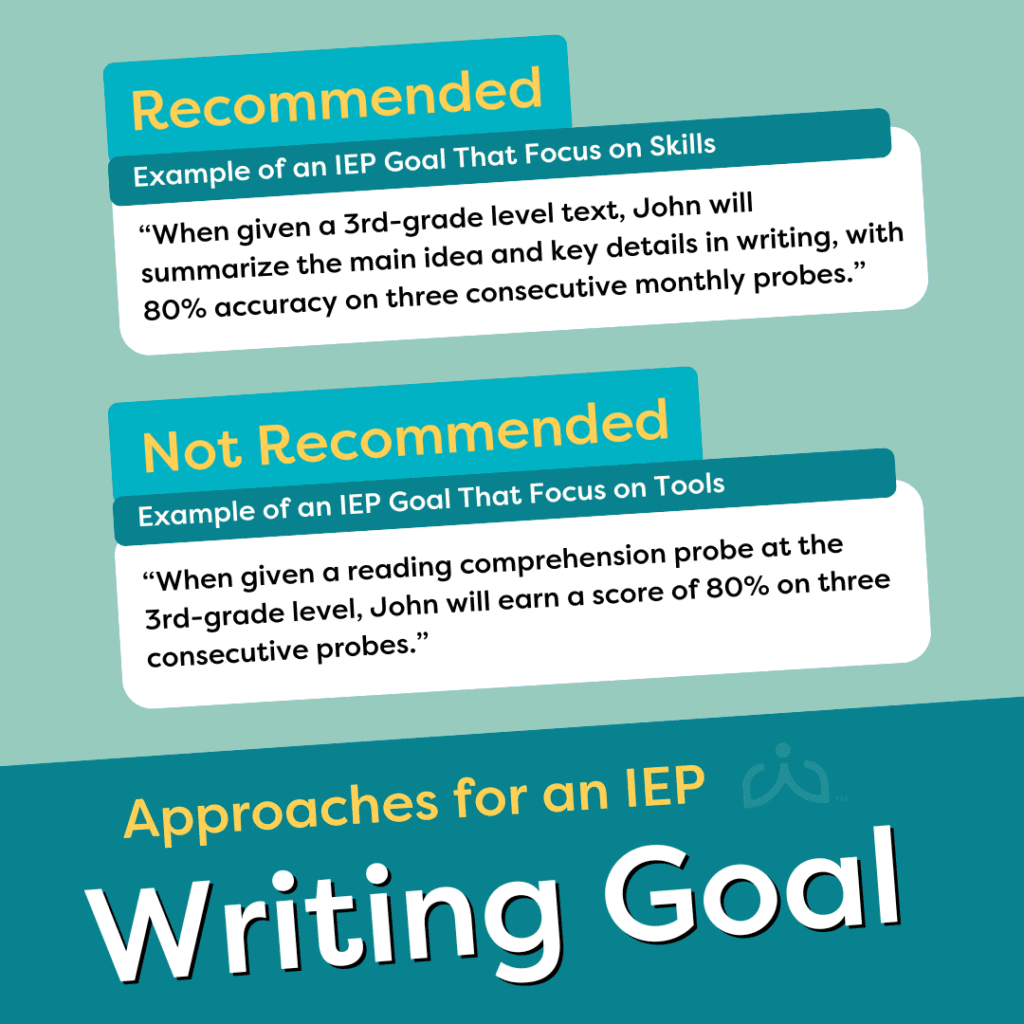

At first glance, the second example may seem clear, but it focuses more on the probe—a monitoring tool—than on the reading skills John needs to develop. It tells us how well he should perform on the assessment, but not which specific reading skills are being targeted.

Instead of focusing the goal on a monitoring tool, we should target the actual skill. The recommended IEP goal, listed at the top of the graphic in the above example, shifts the focus to summarizing—a specific, teachable skill—making it easier to plan instruction.

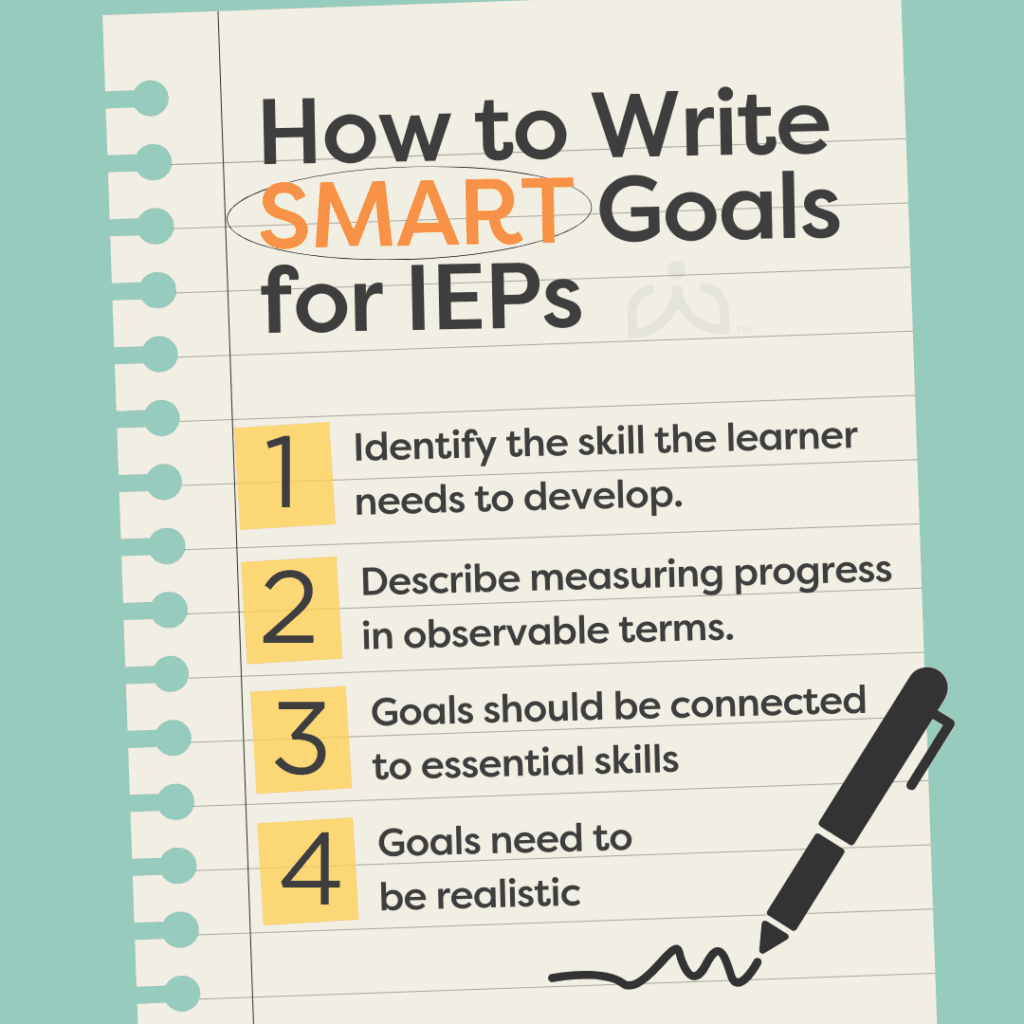

How to Write SMART Goals for IEPs

When members of the team use an agreed upon framework, such as SMART Goals, the final document has a greater chance of being effective and defensible. Here’s how the SMART framework applies to IEP Goals:

- Specific: Identify the skill the learner needs to develop. The focus should align with the needs identified in the most recent evaluation or reevaluation report. For learners with complex needs, the IEP team must prioritize the most essential areas for growth, as trying to address every need via an annual goal may not be realistic.

- Measurable: The goal should describe how progress will be measured in observable terms. In our earlier example, “earning a score” is not observable, but “summarizing the main idea and key details in writing” is.

- Achievable: Goals need to be realistic. If a learner is currently summarizing with 50% accuracy, aiming for 100% mastery within a year might be too ambitious. Instead, a target of 80% might be more reasonable. However, some skills—like safety-related behaviors—may require 100% mastery (e.g., safely crossing the street).

- Relevant: Goals should be connected to essential skills, especially for transition-age learners. Starting at 14 or 16 (depending on the state), transition planning becomes a critical part of the IEP. Goals should align with the learner’s future plans for Post-Secondary Education, Employment, and Independent Living—and, most importantly, the learner should have a say in these discussions.

- Time-bound: IEP goals cover a one-year period, so it’s important to ensure the scope of each goal matches the learner’s profile and abilities. Monitoring progress regularly is crucial. If the learner isn’t making expected progress, the IEP team needs to meet and adjust the plan to help the learner stay on track.

Resources to Support Goal Development

- Identify a learner’s literacy profile

- Pinpoint areas for targeted intervention

- Track progress across various literacy categories

- Communication

- Print Has Meaning

- Concepts About Print

- Alphabetic Principle

- Phonological Awareness

- Language Comprehension

Sample IEP Goals

Sample Goal: “After reading a text with a repeated sentence pattern (e.g., “We saw”), when asked to use the same pattern to write about a self-selected topic, STUDENT will write at least [#] new sentences that follow the pattern across [X] consecutive weekly opportunities.”

Sample Goal: “After the first shared or guided reading opportunity, when presented with [X] sequencing opportunities with different pieces of text and at least 3 events, STUDENT will correctly sequence the events with [%] accuracy across [X] consecutive weekly opportunities.”

Goal Writing Strategies for IEP Teams

Using the SMART framework and resources like Readtopia’s Emergent Literacy Measures, educators can devise goals that are tailored to learners’ unique needs. With such goals in place, instruction becomes targeted, progress monitoring more purposeful, and outcomes better aligned with the learner’s future success.

Author Bio:

The author is not an attorney and this article is not intended as legal advice.