Pitfalls of Using Symbolated Text For Literacy Instruction

From the desk of Maureen Donnelly, M.Ed

Previously In special education, providing students with text supported by symbols was a default practice for helping learners access a curriculum and learn to read. While the intention was good, an established body of evidence confirms that this approach is inconsistent with literacy instruction best practices and the science of reading.

The pitfalls of using symbolated text is gaining traction in many school districts. One administrator recently shared, “Anytime a symbol is added next to a word, the learner’s opportunity to decode that word is removed, therefore they are no longer receiving instruction aligned with the science of reading.”

How Symbol-Supported Text Developed

Symbol-Supported Text:

Helpful for Communication but not for Literacy Instruction

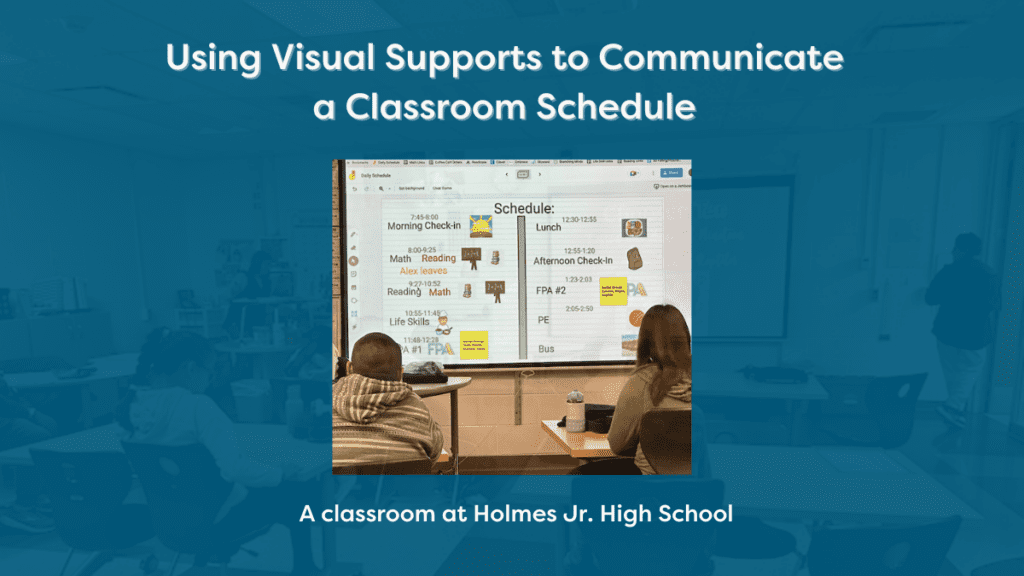

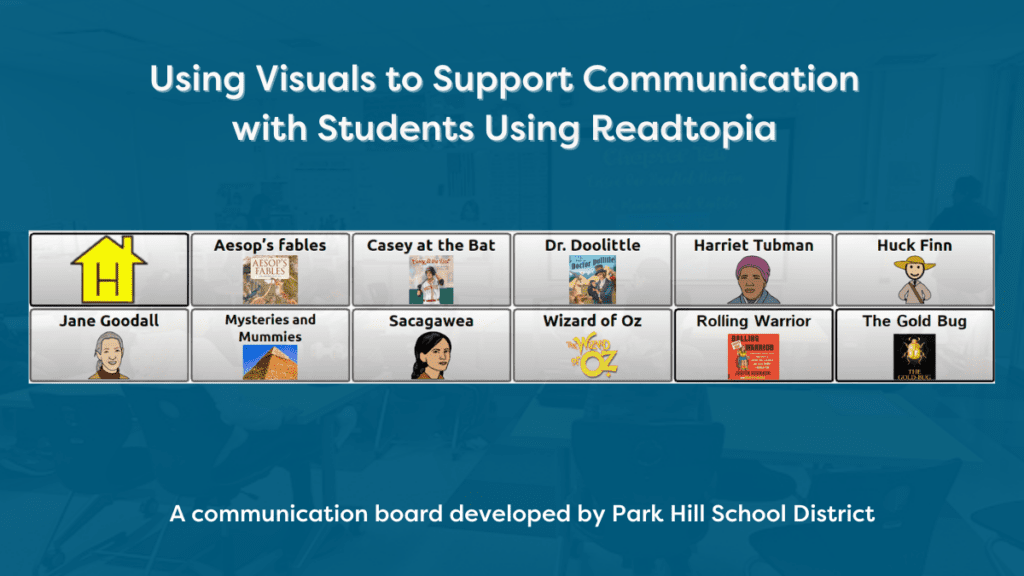

The use of symbols as a visual support in the classroom, at home, and in the community through the use of a communication board or device continues to be an effective method to support expressive communication for those who benefit from augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) as shown in these examples.

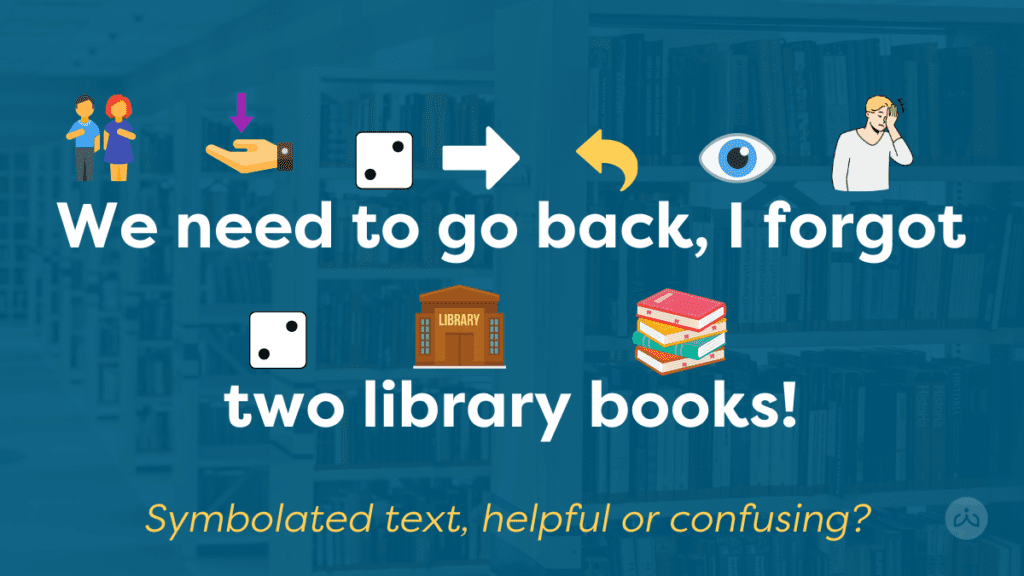

However, it’s important to distinguish between using symbols for communication and using symbols for literacy instruction. This example of a sentence written with symbols illustrates how confusion can occur especially for students learning the difference between the words to and two, and the word back which is discussed further in this article.

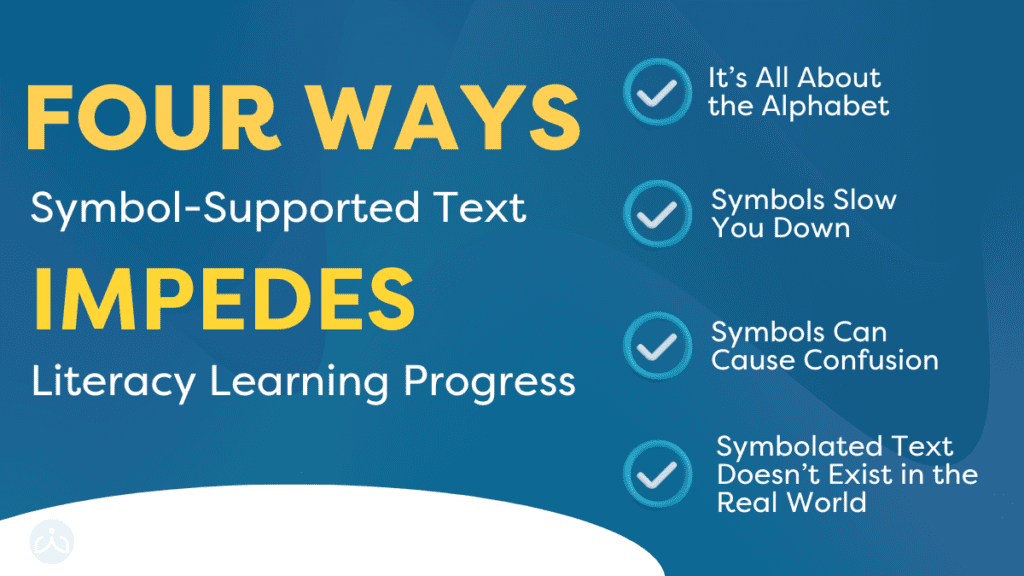

The Research: Four Ways Symbol-Supported Text Impedes Learning Progress

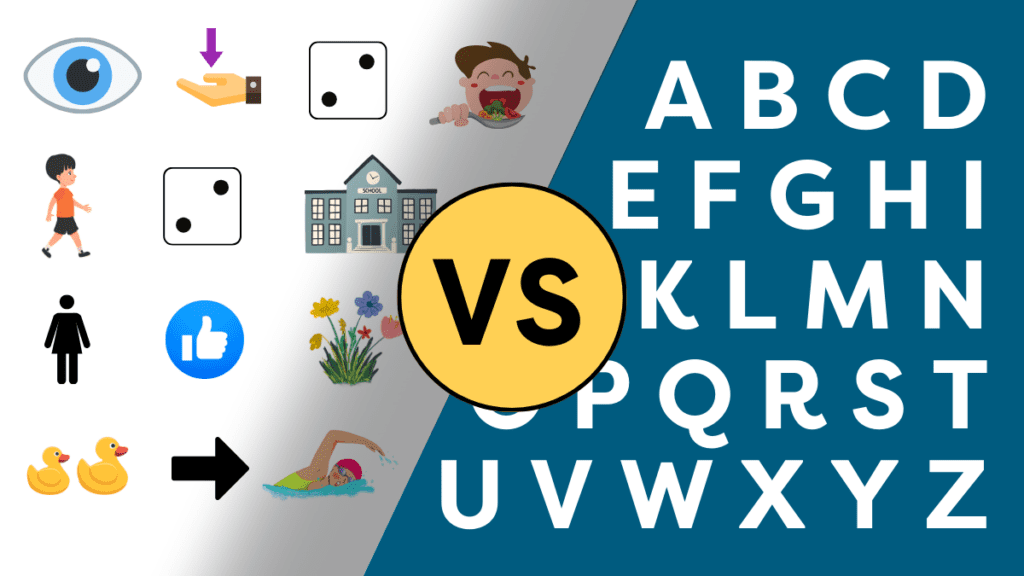

The first answer has to do with the role that the alphabet plays in becoming an independent reader. Knowledge of these 26 letters–and the sounds they represent–is ultimately the only route to anyone’s ability to read, write, and communicate independently and conventionally. As my mentor, Dr. Karen Erickson, the Director of the Center for Literacy and Disability Studies at Chapel Hill, points out, the alphabet is, on its own, a symbol set. So, why not invest our students’ energy in learning to use the symbol set that gives them maximum power and independence in life?

There is more. Let’s keep digging.

In her seminal text, Beginning to Read, Marilyn Jager Adams discusses how critical it is for emergent learners to look at andthrough text. Here is how I understand her claim:

2. Symbols Slow You Down

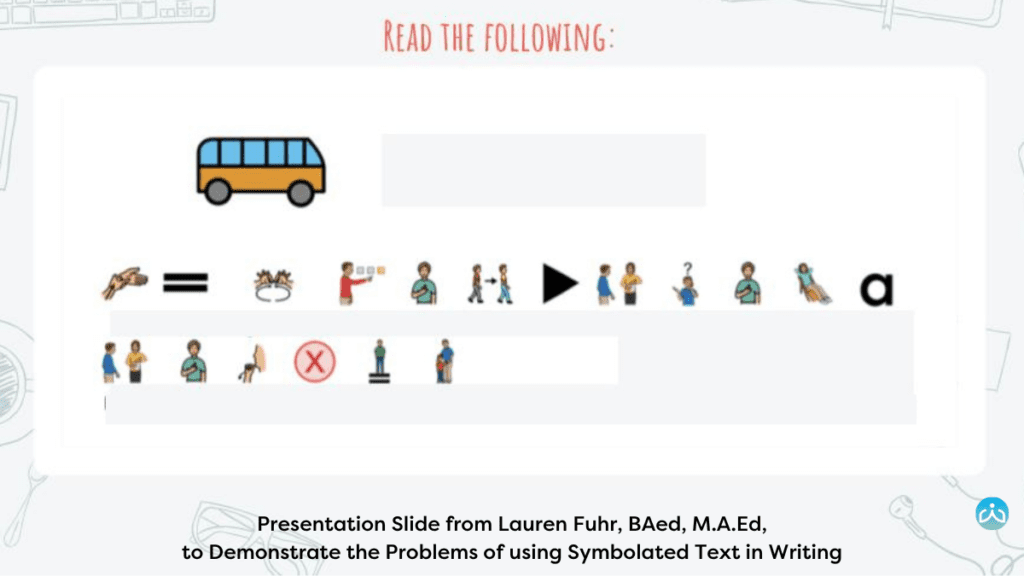

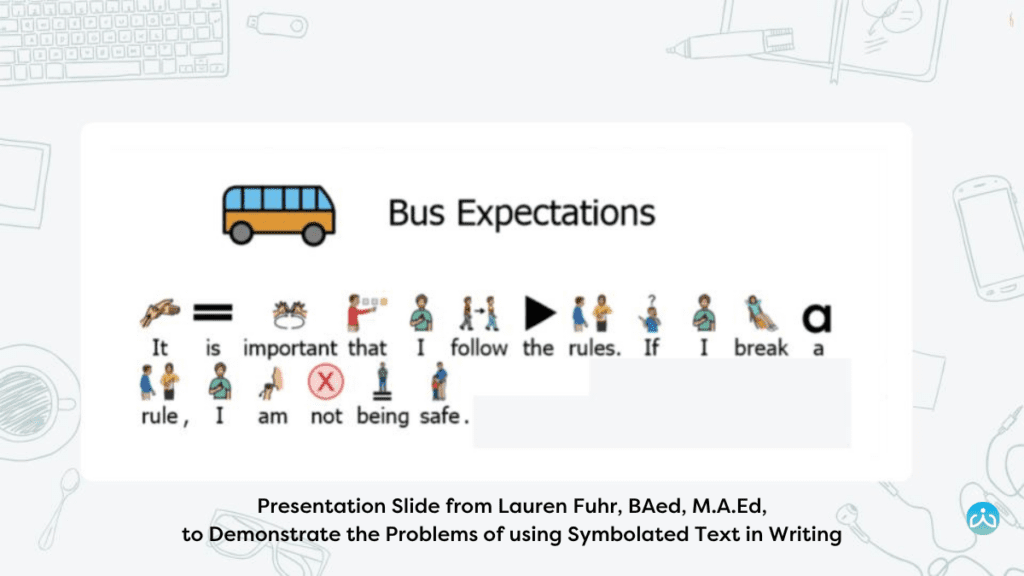

Yet another reason to avoid symbol-supported text is the cognitive load that comes with splitting our focus between pictures/symbols and text. If it’s a competition (which it is), our eyes gravitate toward pictures. Visually, they are more compelling than letters. Consider this example from Lauren Fuhr:

3. Symbols Can Cause Confusion

In the article “Literacy, Assistive Technology, and Students with Significant Disabilities,” Dr. Karen Erickson and her team point out that pictures, paired with text, have the potential to increase confusion when the pictures/symbols represent abstract concepts, have multiple meanings, or serve more than one grammatical function.

The word back is a good example. It’s a noun (a part of the body), a verb (to back a cause), an adjective (the back door), and an adverb (back then). Tools symbolizing text today are not smart enough to incorporate context in their analysis. As a result, learners are left to puzzle meaning out on their own. Similarly, most of our high-frequency words are not easily represented by pictures. How can we meaningfully represent words like, of, and to, with symbols? We can’t.

4. Symbolated Text Doesn’t Exist in the Real World

The last consideration, and perhaps the most important, is this: if we invest our energy in creating symbol-supported materials and then invest our kids’ energy in learning to memorize these symbols, what happens when our learners leave school? There is no symbol-supported Starbucks menu, voting ballot, or job application. As parents and educators, the entirety of our effort is to help our kids be as free as possible to function without us. I’m afraid the rationale for providing symbol-supported text doesn’t lend itself to this goal.

Teach the Alphabet

Maureen Donnelly, M.Ed., a Curriculum Development Manager at Building Wings, is an early childhood educator by training who has worked with students of diverse ages and abilities, from preschool through college. Throughout her 25-year career, Maureen has developed numerous products and written hundreds of books that support the literacy learning needs of beginners.