Inclusive Literacy Instruction:

Defining Comprehensive Literacy “for ALL”

“What does it mean to actually teach children?” Dr. Koppenhaver, co-author of ‘Comprehensive Literacy for All with Erickson’, asks in the beginning of his presentation. Then he elaborates: “Not some children, but ALL children.”

These questions ground Dr. Koppenhaver’s address as he worked his way through examples of curriculum and instruction, including a LETRS kindergarten phonics lesson, to show how inclusive lessons vary from lessons that are less inclusive–and therefore less effective. Watch a recording of Dr. Koppenhaver’s presentation which is also summarized below.

What is comprehensive literacy instruction?

What is literacy inclusion?

While UDL (Universal Design for Learning) can be a useful framework to use, its considerations may need to be specific, says Dr. Koppenhaver, as to who needs those adaptations or when, why, and what we should do if those adaptations don’t work for certain learners.

Examples of non-inclusive instruction

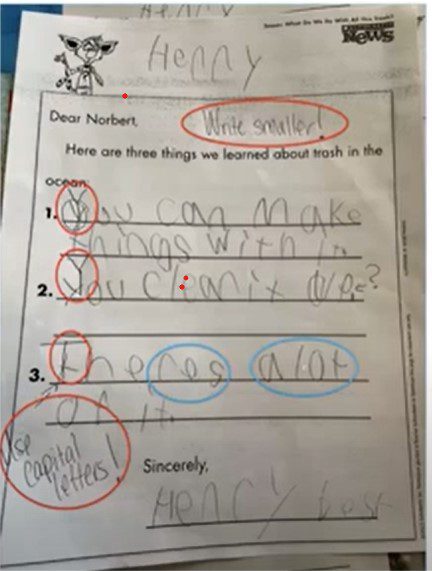

Moving on from definitions and pedagogical ideals, Dr. Koppenhaver shows a worksheet that asks students to list three things they recently learned about trash in the ocean. The student who completed this worksheet, Henry, has listed:

- you can make things with it

- you clean it up

- there’s a lot of it.

In a subsequent example, Dr. Koppenhaver analyzes a LETRS phonics lesson. The purpose of the lesson is to learn the sound and the name of the letter “D,” and the wall behind the teacher is filled with pictures of people’s mouths as they make consonant and vowel sounds.

Dr. Koppenhaver lists the many faulty messages that this lesson sends, which include:

- Emphasizing “watching” and “listening” as essential to learning how to read

- Relying on a confusing “sound wall” of mouths saying sounds in isolation, arranged into a “consonant wall” and a “vowel valley”

- Identifying the lesson’s purpose for reading as learning a single letter, when a reading purpose should always be centered on meaning/comprehension

- Asking students to use their fingers to “tap” out the sounds in the word “dog,” which excludes students who don’t have that motor function

What inclusive instruction looks like

Dr. Koppenhaver explains that instruction is inclusive only when it meets the learners’ needs, be they fine motor, speech, cognition, or attention needs. Inclusive instruction builds upon the learners’ existing understandings and experiences, does not distract from real reading or writing in order to gain attention or engagement, and is delivered efficiently, without impeding any students’ progress within or beyond the activity.

Less inclusive instruction, in contrast, talks about, identifies, or labels language rather than practices language itself. It requires memorization of rules, practices bits of language in isolation without connecting immediately to application in meaningful reading and writing, or requires particular physical or verbal responses.

How to provide inclusive literacy instruction

When designing inclusive instruction, Dr. Koppenhaver encourages educators to:

- Strive for learning opportunities that are fair, not equal, across your current students.

- Provide students with cognitive clarity.

- Stay away from curricula and instruction that emphasize talking about language, identifying aspects of language in isolation, or using rote repetition of rules and examples.

- Maximize student application of learning in contextualized reading and writing.

- Consider your current students’ specific differences.

When it comes to “literacy for all,” ideas and experiences are more important than convention and form, Dr. Koppenhaver maintains. The purpose is to foster genuine engagement around ideas and language. That’s when literacy truly becomes “for all.”